Anatomy of mammary gland

The development of the mammary gland starts early in the fetal life. Already in the second month of gestation teat formation starts and the development continues up to the sixth month of gestation. When the calf fetus is six months, the udder is almost fully developed with four separate glands and a medial ligament, teat and gland cisterns.

The development of milk ducts and the milk secreting tissue take place between puberty and parturition. The udder continues to increase in cell size and cell numbers throughout the first five lactations of the cow, and the milk production capacity increases correspondingly.

To begin studying the anatomy of mammary gland, some anatomical landmarks in the inguinal region must be identified; including the teats, four mammary quarters (two fore and two rear), mammary groove, and fore and rear quarter attachments (suspensory system).

A strong udder suspensory system is required to maintain proper attachments of the gland to the body. The mammary gland is a skin gland, and is external to the body cavity. A Holstein cow may have 50 kg of weight hanging from her body when she walks into the milking parlor to be milked. So the system of ligaments and other tissues which attach the udder to the cow are critical for successful lactation.

There are seven different tissues that provide support for the udder:

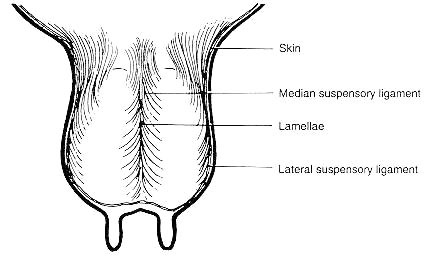

The skin covering the gland, most superficial tissue, is a minor support (Figure 1);

The superficial fascia, or areolar subcutaneous tissue, attaches the skin to underlying the tissue and is another minor support for the cow's udder;

The coarse areolar, or cordlike tissue, forms a loose bond between the dorsal surface of the front quarters and abdominal wall. Weakening of these causes the udder to break away from abdominal wall. This is part of what is referred to as the fore quarter attachments when evaluating dairy cattle conformation. These are important for keeping the fore quarters closely attached to the body wall; however are not the major supports of the udder.

The subpelvic tendon is not actually part of the suspensory apparatus, but gives rise to the superficial and the deep lateral suspensory ligaments. It is not a continuous tissue sheet but is attached to the pelvic bone at several points. This tendon does not support the udder directly, however it gives rise to the lateral suspensory ligaments.

The lateral suspensory ligament are mostly composed of fibrous tissue (with some elastic tissue), arising from the subpelvic tendon. They extend downward and forward from the pubic are. When it reaches the udder it spreads out, continuing downward over the external udder surface beneath the skin and attaching to the areolar tissue (Figure 1).

The deep lateral suspensory ligament (lamellae) is an inner part of the lateral suspensory ligament also arises from the subpelvic tendon, however is thicker than the superficial layer, mostly fibrous tissue. It extends down over the udder and almost enveloping it. The ligament attaches to the convex lateral surfaces of the udder by numerous lamellae which pass into the gland and become continuous with the interstitial framework of the udder. Collectively, the lateral suspensory ligaments provide substantial support for the udder. The left and right lateral suspensory ligaments do not join under the bottom of the udder, and the fibrous nature of these ligaments means that they do not stretch as the gland fills with milk. So, the center of the udder tends to pull away from the body as the gland fills (Figure 1).

The median suspensory ligament is the most important part of the suspensory system in cows. It is composed of two adjacent heavy yellow elastic sheets of tissue that arise from the abdominal wall and that attach to the medial flat surfaces of the two udder halves. The median suspensory ligament has great tensile strength. It is able to stretch somewhat as the gland fills with milk to allow for the increased weight of the gland. It is located at the center of gravity of the udder to give balanced suspension, so that even if rest of the layers are cut away except for the median suspensory ligament, the gland stays balanced under the cow (Figure 1).

Teats

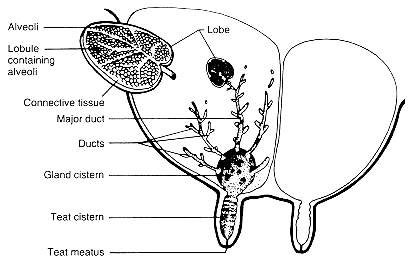

The only exit for the secretion from the mammary gland and the only means for the calf to receive milk are the teats. Teat size and shape are independent of the size, shape or milk production of the udder. Average size for the fore teats is about 6.6 cm long and 2.9 cm (in diameter, and for the rear teats is 5.2 cm long and 2.6 cm in diameter (Figure 2).

About 50% of all cows have supernumerary teats (extra teats). Some of these extra teats open into a "normal" gland, but many do not. Generally they are removed before one year old. A pseudo-teat has no streak canal, and therefore, no connection to the internal structures of the gland.

The only orifice of the gland between internal milk secretory system and the external environment is called streak canal or teat meatus. The teat meatus is made up of three to five convex epithelial projections that lie close together to make a star-shaped slit. The projections are held closed by involuntary sphincter muscles around the orifice. The teat meatus prevents the escape of milk between two milkings and is the main physic protection against bacteria and foreign material, preventing intramammary infection. When a cow is milked, the sphincter muscles relax allowing the orifice to open. The teat meatus remains open for an hour or more after milking. This provides ready access of bacteria to the inside of the mammary gland. Post-milking germicidal teat dips are designed to help minimize the chance of bacteria gaining access to the mammary gland after milking. Keeping cows standing for a time after milking, such as providing access to fresh feed, also helps minimize teat end contamination before the teat meatus closes again. The rate of milking of a cow is partially dependent on the size of the teat meatus. Faster-milking cows usually have a teat meatus of larger diameter.

During the dry period (nonlactating period), the epidermal tissue lining the teat meatus forms a keratin plug that has antibacterial properties, this is an effective seals off the orifice.

Secreting tissue and connective tissue

The mammary gland consists of secreting tissue and connective tissue. The amount of secreting tissue, or the number of secreting cells, is the limiting factor for the milk producing capacity of the udder. It is a common belief that a big udder is related to a high milk production capacity. This is, however, not true in general, since a big udder might include a lot of connective and adipose tissue. The milk is synthesized in the secretory cells, which are arranged as a single layer on a basal membrane in a spherical structure called alveolus (Figure 2). An alveolus is the discrete milk producing unit and the diameter of each alveolus is about 50-250 mm. The lumen of the alveolus is lined by a single layer of secretory epithelial cells. Several alveoli together form a lobule and each lobule contains 150-220 microscopic alveoli. Groups of lobules are surrounded by a connective tissue sheath and form a structure called lobe. The anatomy of this area is very similar to the anatomy of the lung. The milk which is continuously synthesized in the alveolar area, is stored in the alveoli, milk ducts, udder and teat cistern between two milkings. The most part of the milk (60-80%) is stored in the alveoli and small milk ducts, while the cistern contains 20-40%. However, there are relatively big differences between dairy cows when it comes to the cistern capacity.

A large proportion of ducts that are the tubing are presents in the mammary gland. These ducts allow the milk moves from the alveoli to the teat for milk removal. In addition, between the teat and the large ducts are open areas called teat cisterns. A teat cistern is a cavity where milk can collect between two milkings.

The gland cisterns or sinus lactiferous, also called the udder cistern, opens directly into the teat cistern. The gland cistern and teat cistern are separated by the annular fold. The gland cistern function for milk storage (holds 100-400 ml). The gland cistern varies greatly in size and shape. There are often pockets formed in the cistern at the end of the larger ducts.